This is the passage that seems to offend almost everyone:

What many outsiders don't realize is how alienating the decades-long linguistic struggle has been in the once-cosmopolitan city. It hasn't just taken a toll on long-time anglophones, it's affected immigrants, too. To be sure, the shootings in all three cases were carried out by mentally disturbed individuals. But what is also true is that in all three cases, the perpetrator was not pure laine, the argot for a “pure” francophone. Elsewhere, to talk of racial “purity” is repugnant. Not in Quebec.Now it is true that Montreal is more "cosmopolitan" in terms of its ethnic diversity than it once was. Still, relative to Toronto, Montreal has a long way to go. In 2001, visible minorities – the group that Dawson killer Kimveer Gill's family would be considered part of – comprised 13.6% of the population in the Montreal CMA, compared to 36.8% in Toronto. But linguistically it is another story as English is being progressively erased from the face and working life of the city.

What Wong really seems to be probing, however clumsily, is the place that those who are not part of the francophone majority have in Quebec society today. It is certainly foolish to presume that this "otherness" is a driving factor behind the horrendous acts of Kimveer Gill, Marc Lépine or Valery Fabrikant. But is it really so farfetched to suggest that this might be a contributing element to their alienation?

What I find particularly troublesome about Wong's critics is the fact that her hypothesis is dismissed out of hand. They directly attack her, not her arguments. Even Denise Bombardier, a so-called moderate, said something to the effect that Wong had the right to say something stupid. Some defense.

The tendency to circle the wagons on the part of the Quebec intelligentsia whenever someone dares question Quebec is well known. Yet what credibility do a bunch of white francophone journalists, politicians and community leaders, with the odd token, fluently-bilingual anglo or ethnic thrown in for good measure, have when discussing how the province's minorities might feel about their place in Quebec?

To listen to them, Globe and Mail journalists such as Jan Wong or Margaret Wente hate Quebec. They are even accused of fomenting separatist sentiment in the province. But as they ask how could they say such spiteful things, they are oblivious to the fact that they are effectively proving Wong's point. If they are so easily offended by what a Toronto journalist might write, imagine how anglophones and non-francophone immigrants in Quebec might feel when they see their francophone neighbours sporting pins with the slogan "le Québec aux Québécois" or chanting such at the St-Jean Baptiste festivities on June 24th.

Eventually the message gets through. For his part, Jacques Parizeau's outrageous outburst on referendum night about "ethnics and money" was totally redundant. It was already painfully clear that his little country did not include them.

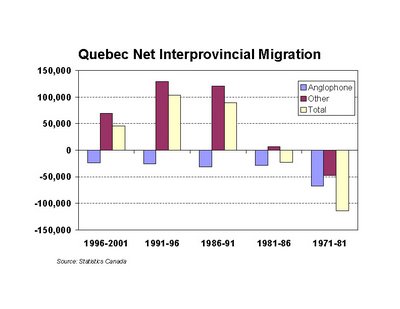

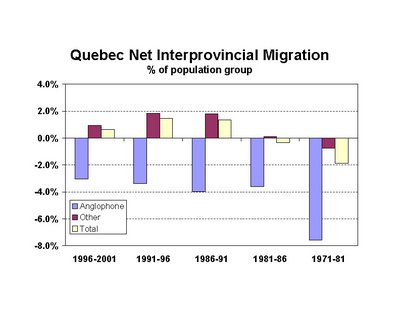

Behind all this psychobabble, though, is one real fact. If English-speakers in Quebec have little or no cause to feel marginalized, then why do they continue to leave the province in large numbers? While Quebec elites feign indignation, English-speaking Quebecers are voting with their feet and leaving the province.

The number of people claiming English as their mother tongue in Quebec dropped more than 25% from 1971 to 2001. Over the same period, the total population of Quebec increased by 20.5%. In light of this apparent demographic mystery, perhaps a little more introspection about the society Quebecers want to build is in order.

The number of people claiming English as their mother tongue in Quebec dropped more than 25% from 1971 to 2001. Over the same period, the total population of Quebec increased by 20.5%. In light of this apparent demographic mystery, perhaps a little more introspection about the society Quebecers want to build is in order.